Private collection, Europe, since the 1950s;

Sale, Christie’s, London, 29 July 2020, lot 15;

Private collection.

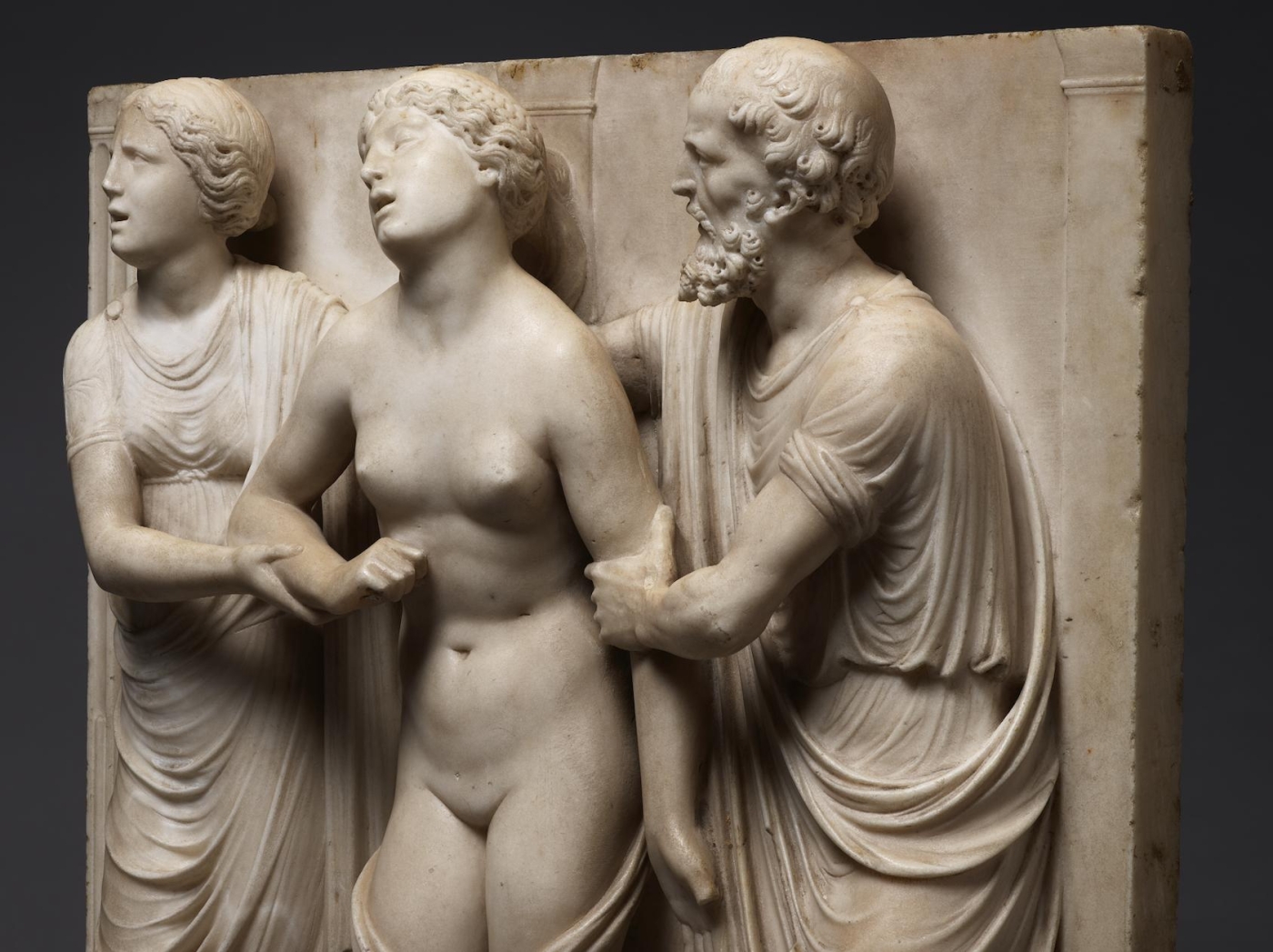

This beautiful and refined relief is a masterpiece of Italian Renaissance sculpture. Previously entirely unknown to scholars, its appearance on the art market in 2020 was one of the most important art-historical discoveries of recent years.

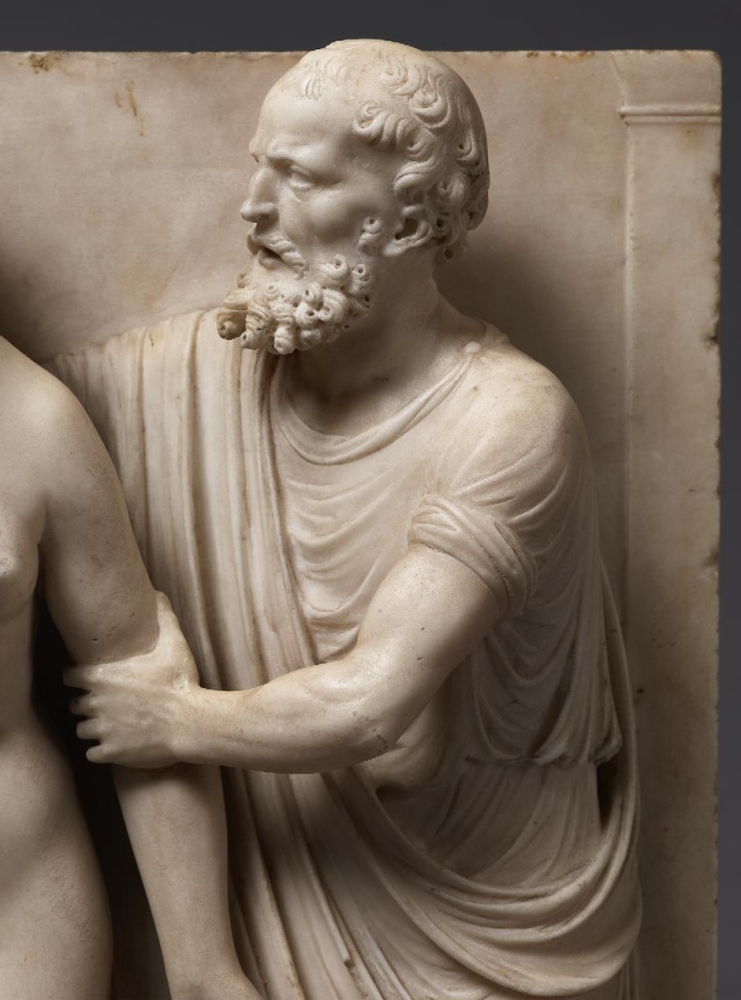

The sculpture depicts the Roman heroine Lucretia as she commits suicide by plunging a dagger into her stomach below her right breast, following her violent rape by Sextus Tarquinius. She is flanked on her left by an elderly man, presumably her father, Spurius Lucretius, and on her right by a young woman, probably her maidservant, who appears to cry out. The figures stand upon a small integral base, curved at the left and right edges, with Lucretius’s left foot projecting over it. Behind the figures are three columns, the one on the left fluted, the others plain, and the beginnings of arches. Holes on the top edge of the relief seem to confirm that there was originally a separately carved top section, which would have completed the arches. Lucretia originally held a small dagger, the hilt of which, now lost, was probably made of metal, inserted into a small hole in her right hand. Other than the loss of the top section, the relief is overall in very good condition, with just some minor losses, such as Spurius Lucretius’s left toes, and the fingers of Lucretia’s left hand. Some areas that would not have been particularly visible have been left unworked – for example, the back parts of Lucretia’s head, or the father’s left thumb.

The story of the noble Roman woman Lucretia, her rape and the subsequent redemption of

her honour through suicide was immensely popular in Italy and elsewhere in Europe during

the Renaissance period. Lucretia was one of a group of mythological and historical women

who were regarded as exemplars of nobility and female virtue and whose stories were

recounted in literature, especially Boccaccio’s tremendously popular De mulieribus claribus, and in art. The Italian retellings of Lucretia’s story were derived from earlier Latin texts,

including Ovid and, in particular, the account given by Livy in his History of Rome (Book I,

chapters 57–9). From the late fifteenth century, Italian translations of Livy’s history of Rome

began to appear, notably an influential edition with woodcut illustrations in Venice in 1493.

The events recounted by Livy and subsequent authors took place in 509 B.C., when Roman

troops were camped outside the city of Ardea during a siege. The group included Sextus Tarquinius, the son of the Roman king, and his kinsman Collatinus. In the course of a

drinking bout, the men began to debate whose wife was the most virtuous, Collatinus loudly

proclaiming that his Lucretia would unquestionably win any such competition, but that they

should test the matter for themselves by riding to visit their respective spouses. The party,

by now the worse for drink, set out for Rome, to find Sextus Tarquinius’s wife and other royal

princesses enjoying a banquet and disporting themselves frivolously. They rode on to

Collatia, where Lucretia was, on the other hand, discovered ‘still in the main hall of her

home, bent over her spinning and surrounded by her maids as they worked by lamplight’.

Taken with her beauty and virtue and, perhaps, smarting a little from the comparison with his

own wife’s behaviour, Sextus Tarquinius became consumed with sexual desire. A few days

later and unbeknown to Collatinus, he again travelled to Collatia, where he was graciously

welcomed as a guest and given a room. Once the household was asleep, Tarquinius crept

to Lucretia’s bedroom with his sword in hand, threatening Lucretia and confessing his

passion for her. When the woman refused to submit, Tarquinius further threatened to kill

both her and a slave, whose body he would place in the bed alongside hers. Faced with the

prospect of utter shame for herself and her family, Lucretia finally submitted. However, after

Tarquinius had left, she quickly sent to Rome for her father, Spurius Lucretius, and to Ardea

for her husband, Collatinus. Each came with a companion, Spurius Lucretius with Publius

Valerius and Collatinus with Lucius Iunius Brutus. Explaining to the men that although her

body had been defiled, her soul remained pure, the disconsolate Lucretia demanded from

them a pledge to punish Sextus Tarquinius: ‘“It is up to you”, she said, “to punish the man as

he deserves. As for me, I absolve myself of wrong, but not from punishment. Let no

unchaste woman hereafter continue to live because of the precedent of Lucretia.” She took a

knife she was hiding in her garments and drove it into her breast. Doubling over, she

collapsed in death.’

Lucretia’s death had profound consequences for Roman history, as Brutus seized the

opportunity of the horrendous circumstances of the rape and dishonouring of Lucretia to

stoke outrage against the ruler of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, and his family. This

led quickly to their expulsion and replacement by a new and long-lasting monarchy.

On its appearance at auction in 2020, the relief was attributed to the Venetian sculptor Antonio Lombardo, whose father, Pietro Lombardo (1435–1515), ran the leading architectural and sculptural workshop in Venice in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, with the active participation of Antonio and his brother, Tullio (c.1455–1532). In 1506 Antonio left Venice for Ferrara, where he worked until his early death in 1516 for Alfonso I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara (1476–1534), one of the greatest patrons of art in Renaissance Italy. The artistic styles of both Antonio and Tullio are based on a refined form of classicism and in many respects are closely similar. It is, nevertheless, possible to distinguish Tullio’s severe and usually rather dry classicism from the fuller and more empathetic style of Antonio. As Anne Markham Schulz has observed, this can best be done by comparing the two reliefs of the Miracle of the Repentant Son and the Miracle of the Speaking Baby, made by Tullio and Antonio respectively for the Chapel of Saint Antony in the Basilica di Sant’Antonio in Padua during the years around 1500–5: ‘a comparison of the brothers’ two reliefs shows Tullio to possess an appreciation of structure and hierarchy analogous to systems of scholastic reasoning, and so obsessive a sense of order, so pronounced a tendency toward abstraction, that Antonio’s composition appears by contrast almost casual’. Other subtle differences can be discerned in the two brothers’ work, including the modelling of draperies, the treatment of hair and the sense of volume in figures.

The attribution of the Death of Lucretia to Antonio when it was offered at auction is very

likely to be correct, although the high degree of symmetry and spatial organisation in the

relief is perhaps more characteristic of Tullio’s approach to sculpture. But the evidence for

attribution to Antonio is compelling: for example, the strong sense of volume in the three

figures, the use of a drill for the hair of the elderly man, the engagement between the

protagonists and the powerful psychological intensity, discussed further below. The relief

may for example be compared with two larger multi-figure reliefs, the Virgin and Child with

Saint George and a Donor from the workshop of Antonio Lombardo, formerly in the Church

of San Domenico in Ferrara, and the relief depicting the Healing of Anianus that

flanks the doorway to one of the entrances to the former Scuola Grande di San Marco in

Venice, paired with Tullio’s relief of the Baptism of Anianus.

Antonio’s most celebrated work is the extensive series of figurative and decorative reliefs made for the studio dei marmi created by Alfonso I d’Este for the Via Coperta of his palace in Ferrara, almost all of which are now in the Hermitage, St Petersburg. Most of the surviving panels, one of which is dated 1508, are largely decorative, but in the Hermitage are two large figurative reliefs depicting The Contest between Minerva and Neptune for the Possession of Attica and The Forge of Vulcan, conceivably made for another room in the Via Coperta. The figure of Vulcan is directly based on the famous antique sculpture of Laocoön, that had been discovered in 1506. Although these reliefs are very different in their conception from the Death of Lucretia, several stylistic parallels are apparent: the drapery of Minerva and that of the woman at left in the Death of Lucretia; the magnificent rendering of nude figures; the handling of the beards in the figures of Vulcan and of Spurius Lucretius in the present relief.